Vector Search and AI Copilots: A New Era for Financial Document Analysis

High-Level Overview

Analyzing lengthy financial documents like SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, 8-K, etc.) and earnings call transcripts is a time-consuming challenge for fintech professionals. Vector search offers a smarter way to sift through these texts by representing documents and queries as high-dimensional vectors that capture semantic meaning. Unlike traditional keyword search, which only matches exact words, vector search retrieves information based on context and intent (How to deploy NLP: Text embeddings and vector search - Elasticsearch Labs). For example, a keyword search for “Apple stock” might return recipe articles about fruit, whereas a vector search understands you mean the company and brings back finance-related content (Exploring Vector Search: Advantages and Disadvantages - Enterprise Knowledge). This semantic approach means you can find relevant insights even if the exact terms don't appear, dramatically improving the speed and accuracy of research.

In tandem, AI copilots (powered by large language models, or LLMs) act as intelligent research assistants. An AI copilot can parse complex financial language, perform calculations, and answer questions in plain English. Integrating a copilot with vector search turns document analysis into a conversational experience. For instance, Boardroom Alpha’s Analyst Copilot lets users ask complex questions about a company’s filings and instantly get summaries, numbers, and red flags extracted from those documents (BA Analyst Copilot - Accelerated Insights from SEC Filings – Boardroom Alpha Help). The copilot uses an LLM to read the retrieved text and highlight insights like changes in risk factors or details about executive compensation. This synergy of vector search and AI enables natural language querying of financial reports – you can ask “What were the main growth drivers this quarter?” and get a direct answer with supporting context, instead of manually hunting through pages of filings.

Key Benefits for Fintech and Investment Professionals

Faster Insights: Vector search delivers highly relevant results from large document sets in seconds (Exploring Vector Search: Advantages and Disadvantages - Enterprise Knowledge). Analysts no longer need to skim hundreds of pages; the most pertinent snippets (e.g. a paragraph about “revenue guidance” or “regulatory risk”) are surfaced immediately, reducing research time and enabling quicker decision-making. This real-time retrieval accelerates the time-to-insight, which is crucial in fast-moving financial markets (Real-time analytics, vector search accelerate time to insights).

Deeper Understanding: Because it’s semantic, vector search captures context that keyword search misses (Exploring Vector Search: Advantages and Disadvantages - Enterprise Knowledge). You can find discussions that use different terminology but mean the same thing – for example, a company might discuss “supply chain headwinds” without using the word “risk”, and a semantic search would still catch it. This ensures investment professionals don’t overlook important information due to jargon differences. It also allows cross-document analysis, like finding common themes across several earnings calls or comparing how multiple companies talk about inflation.

AI-Augmented Analysis: An AI copilot can not only fetch information but also perform analysis on the fly. It can aggregate figures from multiple reports and even do calculations or conversions. For instance, ask “What is the 3-year average revenue growth?” and the copilot could retrieve revenue figures from the last 10-Ks and calculate the CAGR. The copilot can also draft summaries of a 100-page 10-K in a few bullet points. By offloading these tasks, professionals can focus on higher-level analysis and decision-making. The result is an interactive research process where the AI handles grunt work (reading, extracting, calculating) and the human analyst applies judgment.

Improved Consistency & Compliance: With AI assistance, every document is analyzed with the same thoroughness, reducing the chance of human error or oversight. This is especially beneficial for compliance and risk teams in fintech who must ensure nothing important is missed in regulatory filings. Vector searches can be filtered by metadata (company, date, form type) to narrow results, and the copilot can highlight exact passages that answer a query, providing an audit trail of how conclusions were drawn. Such capabilities increase trust in the findings since analysts can always trace back the source in the documents.

Overall, combining vector search with AI copilots is transforming financial document analysis into a faster, more intuitive, and more powerful workflow. Fintech companies and investment firms gain a competitive edge by leveraging these tools to extract insights that would be hard to find otherwise, ultimately making research more efficient and actionable.

Practical Implementation Guide

Implementing a vector search pipeline for financial documents involves choosing the right tools and setting up a workflow for ingesting and querying data. Below is a guide to building a system that can ingest SEC filings and transcripts, index them with embeddings, and enable an AI copilot to answer questions on that data.

Best Tools for Vector Search

A number of vector databases and libraries have emerged to facilitate semantic search. Here are some popular options:

pgvector (PostgreSQL extension): pgvector brings vector similarity search directly into a Postgres database (The 7 Best Vector Databases in 2025 | DataCamp). This is great if you already use PostgreSQL and have moderate-scale needs. You can store embedding vectors as a column in your existing tables and use SQL queries to find nearest neighbors (Choosing vector database: a side-by-side comparison | Hacker News). It eliminates the need for a separate vector store and leverages familiar SQL and RBAC features, making adoption easy for teams with established databases.

FAISS: Facebook AI Similarity Search (FAISS) is an open-source library developed by Meta AI for extremely fast vector search and clustering (The 7 Best Vector Databases in 2025 | DataCamp). It’s a library (in C++ with Python bindings) rather than a server, often used embedded in applications. FAISS excels at handling very large vector sets (millions or even billions of embeddings, even exceeding RAM by using optimized indexes) and offers optional GPU acceleration for lightning-fast queries. If you need high performance and are comfortable building an index in-memory or on-disk, FAISS is a solid choice.

Pinecone: Pinecone is a fully managed cloud vector database service (The 7 Best Vector Databases in 2025 | DataCamp). It abstracts away all the index engineering and scaling — you just push your embeddings via an API, and Pinecone handles storage, replication, and search performance. Pinecone is built for production scale, offering low-latency similarity search and easy integration with ML frameworks. It’s a great option for enterprise use-cases or if you don’t want to maintain your own infrastructure. (Notably, Pinecone was the only vector DB in Fortune’s 2023 AI Innovator list (The 7 Best Vector Databases in 2025 | DataCamp).)

Weaviate: Weaviate is an open-source vector database that can also be used as a managed service (The 7 Best Vector Databases in 2025 | DataCamp). It’s schema-less (you store objects with vectors) and highly scalable, with the ability to handle billions of objects. Weaviate provides a lot of out-of-the-box modules – for example, you can plug in OpenAI or Cohere to generate embeddings, or use built-in classifiers. It supports hybrid search (combining keyword and vector queries) and offers advanced features like data clustering and filters. Weaviate’s focus on scalability and extensibility makes it a good fit for large projects or those requiring integration of custom ML models.

DeepSeek: DeepSeek-R1 is an open-source AI model designed specifically for search and Retrieval Augmented Generation workflows (Use DeepSeek with Amazon OpenSearch Service vector database and Amazon SageMaker | AWS Big Data Blog). While not a vector database itself, it pairs with vector stores (like those above) as the “brain” that understands queries and generates answers. You can deploy DeepSeek as your LLM/copilot that sits on top of a vector index: the vector DB finds relevant text and DeepSeek produces a rich answer or summary. It’s optimized for complex reasoning tasks and is a cost-effective alternative to using a proprietary LLM. For example, Amazon integrated DeepSeek with OpenSearch (their vector-capable search service) to power a QA system that answers user queries based on internal documents (Use DeepSeek with Amazon OpenSearch Service vector database and Amazon SageMaker | AWS Big Data Blog). Fintech teams looking for an open-source chat model to complement their vector search may consider DeepSeek or similar models.

Other noteworthy tools: Chroma (an open-source Python vector store focused on simplicity), Milvus (a distributed vector DB from Zilliz, built for billion-scale), Qdrant (open-source, with efficient indexing and filtering), and Vespa (Yahoo’s big data search engine that supports vectors) are also widely used. The best choice depends on your scale, budget, and integration needs. For quick prototypes or moderate data sizes, adding pgvector to Postgres or using a local FAISS index may suffice (Choosing vector database: a side-by-side comparison | Hacker News) (Choosing vector database: a side-by-side comparison | Hacker News). For large-scale or real-time applications, a dedicated vector DB (managed or self-hosted) can provide the performance and features required.

Setting Up Vector Search with Embeddings

Once you’ve picked a tool, the implementation follows a common pipeline. The goal is to convert unstructured financial text into vector embeddings and load them into a search index. Here’s a step-by-step example pipeline for SEC filings and transcripts:

Data Ingestion and Parsing: Gather the documents you want to index. For SEC filings, you might pull 10-K, 10-Q, 8-K forms from the SEC EDGAR system (which provides filings in HTML or text). Earnings call transcripts can be obtained from investor relations sites or financial databases. Parse these files into plain text, stripping out HTML tags or metadata. It’s often useful to break out sections (e.g., Risk Factors, MD&A, Financial Statements) since analysts might want to search within those specifically.

Text Chunking: Very long documents need to be split into smaller chunks before embedding. Vector models have input size limits (and also, smaller chunks yield more granular search results). A common approach is to split by paragraphs or slide windows of ~500 tokens each (Understanding and Applying Vector Databases to Supercharge your SOC with AI & Copilot for Security - Security Risk Advisors). For example, a 60-page 10-K can become hundreds of chunks, each corresponding to a paragraph or section. Store references so you know which document and section each chunk came from (for later displaying results or citations).

Embedding Generation: Choose a language model to transform each text chunk into an embedding vector. You could use a pre-trained model like OpenAI’s text-embedding-ada-002 or open-source alternatives such as SentenceTransformers (e.g.,

all-MiniLM-L6-v2) or FinBERT for financial text. Each chunk (a few sentences) becomes a high-dimensional vector (typically 384 to 1536 dimensions). This numeric vector captures the semantic essence of the text (Understanding and Applying Vector Databases to Supercharge your SOC with AI & Copilot for Security - Security Risk Advisors) – for instance, two chunks both discussing market competition will end up with vectors close to each other in this vector space.Indexing in a Vector Database: Take the embeddings and load them into your vector search tool of choice. In PostgreSQL with pgvector, you’d insert them into a table with a

VECTORcolumn and add an index. In Pinecone or Weaviate, you’d use their client libraries to upsert the vectors with an ID and metadata (like document name, section, etc.). For FAISS, you’d build an index structure in memory or on disk (flat L2 index, HNSW, IVF, etc., depending on your trade-offs for speed vs. accuracy). The vector database will organize these vectors to enable efficient nearest-neighbor searches, often using algorithms like HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World graphs) to approximate the results quickly.Query Interface (Vector Search): With the index ready, your application can accept user queries. A query like “What are the biggest risks mentioned by Company X?” is passed to the same embedding model to produce a query vector. The vector DB is then queried for the nearest neighbor vectors – effectively retrieving the document chunks that are most semantically similar to the question. This vector similarity search returns, say, the top 5-10 chunks that likely contain information about the company’s risks. Unlike a keyword search, it can find relevant text even if the query phrasing doesn’t exactly match the text (perhaps the filing said “principal dangers to our business” instead of “biggest risks”) (How to deploy NLP: Text embeddings and vector search - Elasticsearch Labs).

AI Copilot Integration (LLM Response): The final step is optional but highly valuable – feed the retrieved text chunks into an AI copilot (an LLM) to formulate a useful answer or analysis for the user. Typically, the user’s question and the top retrieved chunks are concatenated into a prompt for a GPT-style model. The model then generates a response like: “Answer: The company’s biggest risks include reliance on a sole supplier and potential regulatory changes in Europe (as noted in the Annual Report’s Risk Factors section).” The copilot effectively performs a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG): it uses the vector store as a knowledge base to ground its answers in actual data (Building LLM Applications With Vector Databases). This reduces hallucination and ensures that if the user asks for a number or fact, the model has the source context to draw from rather than guessing. The copilot can also cite which document or section it used, adding transparency. For financial calculations, the copilot might even extract figures from those contexts and calculate on the fly (for example, subtracting this quarter’s revenue from last quarter’s to answer a growth question).

Putting it Together – Example: Imagine an analyst wants to compare how two competitor companies discuss inflation in their 10-Ks. The system would embed all 10-K sections from both companies into the vector index. The analyst asks: “How does Company A’s view on inflation compare to Company B’s?” – the query vector might retrieve a paragraph from Company A’s MD&A about “rising input costs due to inflation” and one from Company B’s risk factors about “inflationary pressures on operating expenses.” The copilot LLM could then summarize: “Company A notes that inflation increased their raw material costs by 5%, while Company B warns that inflation could squeeze margins unless they raise prices.” In seconds, the analyst has a concise, side-by-side insight that would have taken much longer to find by manually reading two reports.

Code Sample: Vector Search Workflow

To make this more concrete, below is a simplified Python example demonstrating a vector search workflow using an open-source embedding model and FAISS (for illustration). In practice, you’d replace the example documents with actual filing text and possibly use a different vector store, but the process would be similar:

# Install sentence-transformers and faiss via pip if needed:

# pip install sentence-transformers faiss-cpu

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

import faiss

import numpy as np

# Sample financial text snippets (in practice, these come from SEC filings or transcripts)

docs = [

"In 2024, the company achieved a 15% increase in net revenue, driven by expanding market share.",

"Management noted several risks, including supply chain disruptions and potential regulatory changes in Europe."

]

# 1. Embed each document chunk into a vector

model = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2') # a pretrained sentence embedding model

doc_vectors = model.encode(docs) # shape: (2, 384) for 2 docs with 384-dim embeddings

# 2. Create a FAISS index and add the document vectors

index = faiss.IndexFlatL2(doc_vectors.shape[1]) # L2 distance (could also use cosine similarity)

index.add(np.array(doc_vectors, dtype='float32'))

# 3. Embed a query and search for similar documents

query = "What risks did the company mention?"

query_vec = model.encode([query])

D, I = index.search(np.array(query_vec, dtype='float32'), k=1) # find the top-1 nearest neighbor

match_idx = I[0][0]

print("User query:", query)

print("Top match:", docs[match_idx])

Running this code would output something like:

User query: What risks did the company mention?

Top match: Management noted several risks, including supply chain disruptions and potential regulatory changes in Europe.

As shown above, the query “What risks did the company mention?” gets vectorized and the system finds the closest snippet, which indeed contains the word "risks" and lists specific examples (supply chain, regulatory). In a real application, you might take the docs[match_idx] text and pass it to an LLM along with the question to generate a more elaborate answer or summary for the end user. This snippet demonstrates the core mechanism of vector search: converting text to vectors and using nearest-neighbor lookup to fetch relevant pieces of information.

Integration Tips for an AI Copilot

Integrating an AI copilot with your vector search can be done through frameworks or custom code:

LangChain or LlamaIndex: These open-source frameworks provide convenient abstractions for building RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) pipelines. You can define a document index (e.g., backed by Pinecone, Weaviate, etc.) and then ask questions to an LLM with automatic retrieval. LangChain, for example, has chains that do: embed query -> search vector store -> stuff results into prompt -> call LLM -> return answer. This saves you from writing glue code and handles a lot of the prompt engineering for you.

Meta-data and Filters: Financial documents have rich metadata (company name, filing date, section type). Leverage vector DB features to filter queries. For instance, if you only want to search within a specific company’s documents or within 8-K current reports, you can add those as filter conditions alongside the vector similarity search (Vector search - Azure AI Search | Microsoft Learn) (Vector search - Azure AI Search | Microsoft Learn). Many vector databases support hybrid queries (vector + boolean filters) which is extremely useful in finance where you often want to constrain the search.

Continuous Updating: Fintech use-cases often involve continuous data (new filings each quarter, new transcripts each earnings call). Design your pipeline to allow updates – e.g., a new 10-Q comes in, you parse, chunk, embed, and upsert into the index. Vector indices like Pinecone handle upserts in real-time, whereas with FAISS you might need to rebuild or use an IVF index to append. Keeping the index fresh ensures your copilot always has the latest information (you wouldn’t want it answering based on last year’s report when a newer one is available!).

Accuracy and Verification: While AI copilots are powerful, in finance it's crucial to verify critical outputs. Encourage the habit of checking the source. The copilot can be prompted to say “According to the 2023 10-K, ...” and you might even have it output a snippet or reference page numbers. This transparency helps build trust with users (especially important if the tool is used for compliance or investor communications). Additionally, be aware of the limitations – if the question is outside the scope of the documents (e.g., asking for future predictions), the copilot might speculate. Setting expectations and guiding the model with system prompts (like “If you don’t know, say you don’t have that information”) is a good practice.

By following the above steps and tips, fintech teams can set up a robust vector search system tailored to financial documents. With the right pipeline in place, your AI copilot can act as an on-demand financial analyst, ready to answer questions or perform research 24/7, powered by the knowledge stored in filings and transcripts.

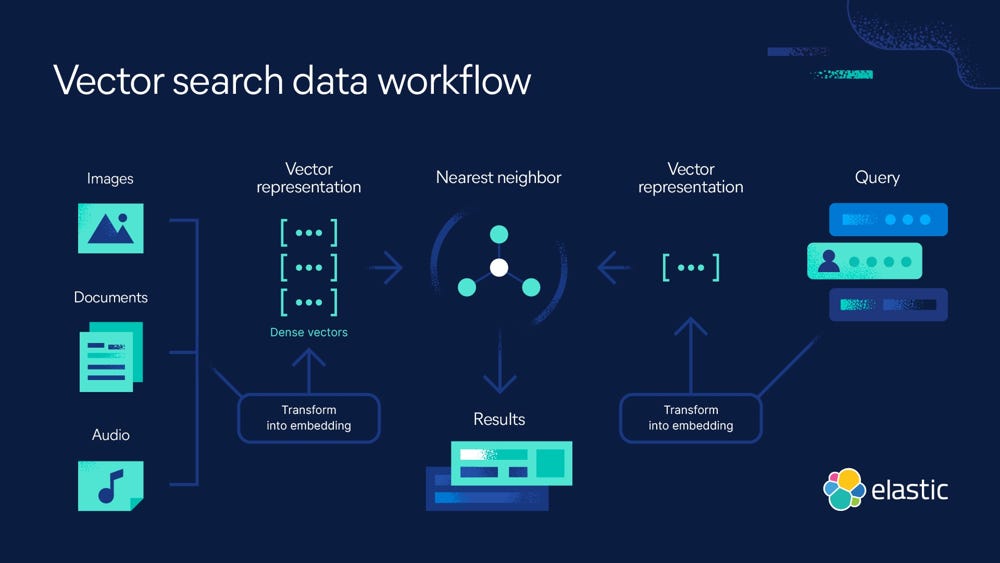

How Vector Embeddings Power Semantic Search

(What are Vector Embeddings? | A Comprehensive Vector Embeddings Guide | Elastic) Vector search workflow. This diagram shows how various data sources (text, images, audio) are converted into dense vector embeddings which populate a vector index. In the context of financial documents, think of each “Document” as a chunk of an SEC filing or transcript that has been transformed into a numeric vector. Similar vectors (e.g. two passages both about interest rate risk) cluster near each other in the vector space. When a user makes a query (right side), the query is also transformed into a vector using the same embedding model. The vector search engine then finds the nearest neighbor vectors in the index – i.e. the document chunks most related to the query. Those results are returned to the user (or passed to an AI copilot for answer synthesis). The key idea is that semantic similarity in meaning translates to proximity in vector space (How to deploy NLP: Text embeddings and vector search - Elasticsearch Labs), allowing the system to retrieve relevant information even if exact keywords don’t match.

Architecture of an AI-Powered Financial Document Search System

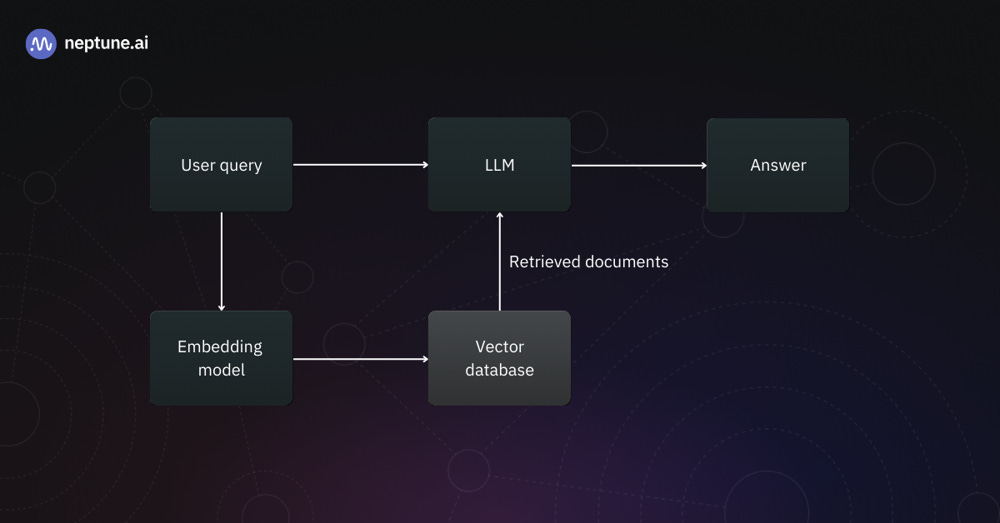

(Building LLM Applications With Vector Databases) An AI-enabled financial document search system typically has a pipeline like this. First, the user query is passed through an embedding model to convert it into a vector representation. That vector is used to query the vector database (which contains embeddings of all the financial document chunks). The vector DB performs a similarity search and returns the most relevant document vectors (with the original text). These retrieved documents (or snippets) are then combined with the user’s query as context for the LLM (AI copilot). The LLM processes this augmented prompt and produces a final answer or analysis, which is shown to the user (Building LLM Applications With Vector Databases). In our case, the “documents” are pieces of SEC filings or transcripts, so the answer might be a paragraph summarizing a company’s risk factors or a numeric calculation drawn from a financial statement. This retrieval-augmented generation architecture ensures the copilot’s responses are grounded in the actual content of your filings, making them more accurate and trustworthy. The flow is end-to-end: from raw data to embedding, to search, to AI-generated insight.

Conclusion

Vector search combined with AI copilots is poised to revolutionize how financial professionals interact with data. By leveraging embeddings, we can unlock semantic search capabilities that make it far easier to pinpoint relevant information in massive collections of SEC filings and earnings calls. This means less time lost in CTRL+F or manually reading, and more time gleaning insights that matter. AI copilots bring a conversational and analytical layer on top of this – handling everything from summarizing a 10-K, extracting key metrics, to performing calculations and comparisons across documents. The result is a research process that is engaging, efficient, and thorough.

Key takeaways include the importance of choosing the right vector database for your needs, the steps to build a pipeline (ingest, chunk, embed, index, query), and how an AI copilot can be integrated to turn search results into meaningful answers. Implementing such a system is within reach thanks to mature tools like pgvector, FAISS, Pinecone, Weaviate, and others, plus frameworks that tie it all together. Companies are already seeing the benefits – from accelerated due diligence to proactive risk monitoring – as these technologies handle the heavy lifting of data mining.

Looking ahead, the future potential of AI copilots and vector search in fintech is immense. We can expect even tighter integration of real-time data (imagine querying live streaming financial news in the same way), more specialized financial language models (perhaps trained on accounting or legal text for even deeper understanding), and features like automated report generation. For example, a copilot might proactively alert you: “The latest 10-Q of Company X added a new risk factor about cybersecurity – here’s a summary,” as soon as the filing drops. Additionally, advancements in multimodal embeddings could allow linking textual filings with related data like stock price movements or analyst reports in vector space, enabling even richer analysis.

In summary, vector search and AI copilots empower professionals to analyze financial documents with unprecedented speed and intelligence. Adopting these tools now can give fintech companies and investment analysts a significant edge, turning the deluge of financial data from a burden into a goldmine of insights. The technology is here – it’s time to let your very own AI copilot take the wheel for your financial document research, and experience the efficiency gains firsthand.